The Spread of Covid in Prisons

June 26, 2020

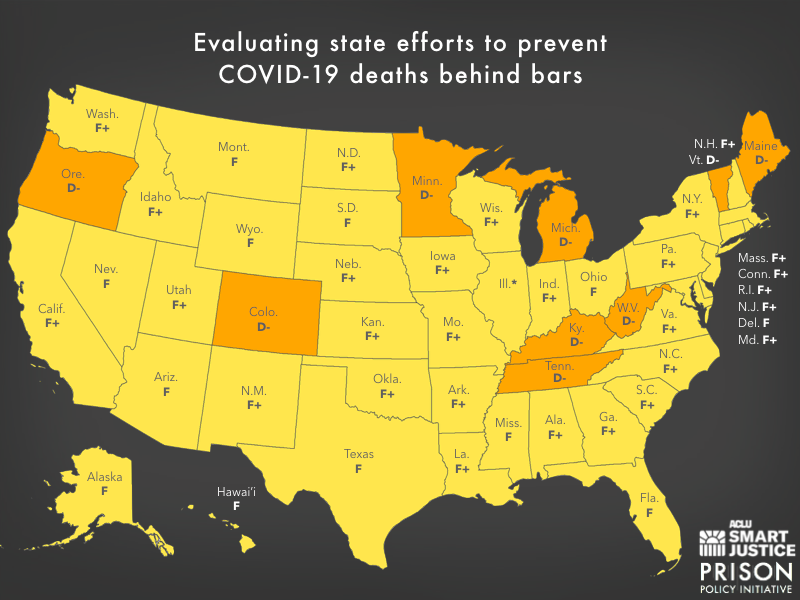

This week we have learned that the coronavirus is ripping through much of the southern and southwestern sections of the U.S. The press and media is full of stories of how the virus is spreading exponentially in these parts of the country. But we also learned this week that on the whole prisons have failed in dealing with the virus. This week Prison Policy Initiative released a report grading each state's response to Covid-19 in their prisons. According to this report most states have failed in protecting their prison populations. Here is the report:

Failing Grades: States’ Responses to COVID-19 in Jails & Prisons

By Emily Widra and Dylan Hayre

June 25, 2020

When the pandemic struck, it was instantly obvious what needed to be done: take all actions possible to “flatten the curve.” This was especially urgent in prisons and jails, which are very dense facilities where social distancing is impossible, sanitation is poor, and medical resources are extremely limited. Public health experts warned that the consequences were dire: prisons and jails would become petri dishes where, once inside, COVID-19 would spread rapidly and then boomerang back out to the surrounding communities with greater force than ever before.

Advocates were rightly concerned, given the long-standing and systemic racial disparities in arrest, prosecution, and sentencing, that policymakers would be slow to respond to the threat of the virus in prisons and jails when it was disproportionately poor people of color whose lives were on the line. Would elected officials be willing to take the necessary steps to save lives in time?

When faced with this test of their leadership, how did officials in each state fare? In this report, the ACLU and Prison Policy Initiative evaluate the actions each state has taken to save incarcerated people and facility staff from COVID-19. We find that most states have taken very little action, and while some states did more, no state leaders should be content with the steps they’ve taken thus far. The map below shows the scores we granted to each state, and our methodology explains the data we used in our analysis and how we weighted different criteria

| State | Final score | Letter grade | State | Final score | Letter grade | State | Final score | Letter grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 16.39 | F+ | Louisiana | 16.30 | F+ | Ohio | 12.63 | F | ||

| Alaska | 13.79 | F | Maine | 21.22 | D- | Oklahoma | 15.36 | F+ | ||

| Arizona | 9.36 | F | Maryland | 16.28 | F+ | Oregon | 21.23 | D- | ||

| Arkansas | 20.38 | F+ | Massachusetts | 20.99 | F+ | Pennsylvania | 19.16 | F+ | ||

| California | 18.36 | F+ | Michigan | 25.82 | D- | Rhode Island | 15.51 | F+ | ||

| Colorado | 23.37 | D- | Minnesota | 23.32 | D- | South Carolina | 15.58 | F+ | ||

| Connecticut | 14.50 | F+ | Mississippi | 12.29 | F | South Dakota | 11.94 | F | ||

| Delaware | 13.71 | F | Missouri | 19.77 | F+ | Tennessee | 26.35 | D- | ||

| Florida | 9.04 | F | Montana | 13.08 | F | Texas | 12.10 | F | ||

| Georgia | 15.06 | F+ | Nebraska | 16.48 | F+ | Utah | 16.69 | F+ | ||

| Hawai’i | 10.41 | F | Nevada | 12.30 | F | Vermont | 23.65 | D- | ||

| Idaho | 14.63 | F+ | New Hampshire | 14.19 | F+ | Virginia | 16.62 | F+ | ||

| Illinois | n/a | n/a | New Jersey | 19.93 | F+ | Washington | 19.28 | F+ | ||

| Indiana | 14.53 | F+ | New Mexico | 17.62 | F+ | West Virginia | 23.59 | D- | ||

| Iowa | 17.45 | F+ | New York | 18.11 | F+ | Wisconsin | 16.75 | F+ | ||

| Kansas | 17.61 | F+ | North Carolina | 14.48 | F+ | Wyoming | 8.15 | F | ||

| Kentucky | 23.90 | D- | North Dakota | 16.78 | F+ |

The results are clear: despite all of the information, voices calling for action, and the obvious need, state responses ranged from disorganized or ineffective, at best, to callously nonexistent at worst. Even using data from criminal justice system agencies — that is, even using states’ own versions of this story — it is clear that no state has done enough and that all states failed to implement a cohesive, system-wide response.

In some states, we observed significant jail population reductions. Yet no state had close to adequate prison population reductions, despite some governors issuing orders or guidance that, on their face, were intended to release more people quickly. Universal testing was also scarce. Finally, only a few states offered any transparency into how many incarcerated people were being tested and released as part of the overall public health response. Even in states that appeared, “on paper,” to do more than others, high death rates among their incarcerated populations indicate systemic failures.

The consequences are as tragic as they were predictable: As of June 22, 2020, over 570 incarcerated people and over 50 correctional staff have died and most of the largest coronavirus outbreaks are in correctional facilities. This failure to act continues to put everyone’s health and life at risk — not only incarcerated people and facility staff, but the general public as well. It has never been clearer that mass incarceration is a public health issue. As of today, states have largely failed this test, but it’s not too late for our elected officials to show that they can learn from their mistakes and do better.

Note that both Maryland and Virginia were given failing grades for their attempts to protect prison populations. Maryland and Virginia residents need to contact Governors Hogan and Northam urging them to release more people incarcerated, especially those nearing release, those with underlying medical conditions, and those who are 60 years old or older. We urge you to leave a phone message for Gov Hogan at 410-974-3901 or 1-800-811-8336. You can leave a phone message for Gov Northam at (804) 786-0000 and ask for the Governor's office. Urge them to release inmates nearing release within a year, people with underlying medical conditions, and those who are 60 years old or older. Ask them to provide more PPP to both inmates and staff as well as sufficient cleaning supplies and gloves.